The company and the labour movemement

Though in the years around the turn of the century, some social reforms were introduced. For example, the temperance movement was allowed to use a room for its meetings. But all trade union and political activities were forbidden on the company’s premises.

Travelling socialist agitators sometimes visited Ljusne and made attempts to persuade the workers to organise. Ljusne’s workers were influenced both by this and by the trade union activity that had previously blossomed in the areas around Söderhamn. Therefore eventually the workers of Ljusne establisheda political youth club. Ljusne-Woxna’s management disapproved of the activities and the club had to hold their meetings in secret.

In 1904 the club joined the Social Democratic Youth League under the name Ljusne-Ala Social Democratic Youth Club. Membership rapidly increased, from the initial handful to over 200 members in the early summer of 1905.

A crucial telegram

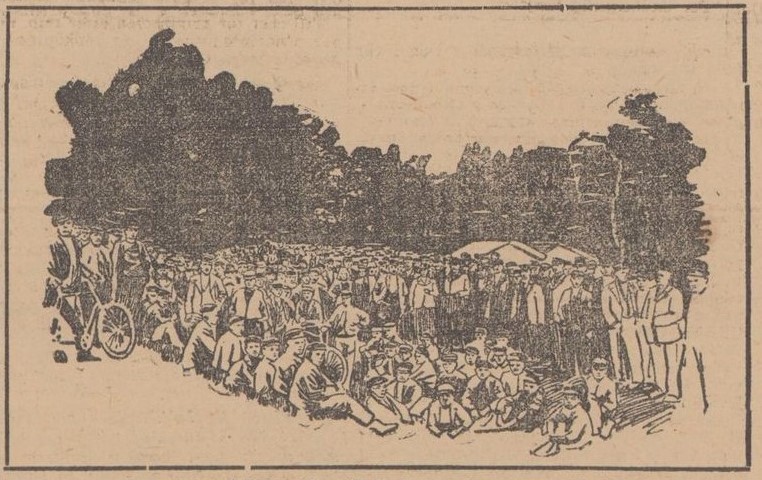

In the summer of 1905, the Ljusne-Ala Social Democratic Youth Club planned an inaugural party for its new banner. They again approached Ljusne-Woxna management and asked for access to a meeting space, but were met with an outright rejection. Therefore the party was held on the Fejan commons, land not owned by the company. On the occasion of the party, a telegram was sent to King Oscar II to pay tribute to him for the successful resolution of the Swedish-Norwegian Union crisis. The telegram read:

Your Royal Majesty!

Fifteen hundred poor workers at Ljusne and Ala gathered for a festive occasion, for want of another place along the highway, to send Your Majesty and the Government heartfelt greetings and a heartfelt thank you for the wisdom and love of peace shown. The memory of it shall not be long forgotten by the people.

C. J. Lindahl/Aug. Gillberg

The real purpose of the telegram was to draw the King's attention to the fact that the workers in Ljusne were not allowed to meet in the company’s premises but rather had to assemble along the highway and that this was a wrong committed by Walther von Hallwyl and the company’s management. Oral history has it that the King then rebuked Walther von Hallwyl for the way he treated his employees.

The company management’s reaction was fury. Less than a week later, six workers were summarily dismissed, among them the signer of the telegram, August Gillberg. Contentious rhetoric soon arose between the two local newspapers: the conservative Söderhamns Tidning, which sided with the company, and the radical Söderhamns-Kuriren which sided with the workers.

Closing down?

In August 1905, rumours began to circulate that the sawmill enterprise would be shut down. Many employees blamed the Youth Club and their telegram. The outrage was so great that August Gillberg, as author of the telegram, was forced to emigrate to America. The speculation about the closure and the loss of hundreds of jobs attracted a lot of attention in the press, locally as well as at the national level.

There was much speculation in the press about the reasons for the pending closure. Was the sawmill not as profitable as before? Or was it the behavior at Fejan by the workers that was the reason? The criticism of Walther von Hallwyl was quite sharp, focusing on the fact that he actually was a foreigner. He was said to be a controversial person and his behaviour completely alien to Sweden’s free society and social system that respected rights. Perhaps this criticism contributed to the fact that he began after this to seriously think about retiring.

The first cutbacks

In January 1906, the company took out an advert in the local press to announce that it would be reducing operations at the sawmill over the course of the following year. Sawmill workers were encouraged to seek work elsewhere. It was also stated that, as a thank you for their long and faithful service, some older workers would be receiving an old-age pension.

In July of the same year, operations managers Lindström estimated that a maximum of 400,000 trees (equivalent to 8,000 standards) could be felled annually in the company’s forests in the period still covered by the timber harvesting rights. The Board of Directors’ 1907 Management Report stated that continuing with their prudent management of the forests it would not have been possible to obtain sufficient timber from the company’s own forests, which is why it was assessed to be necessary to shut down the sawmill operations.

The Norrland issue

The fact that our forestry industry in general is not founded on sustainable forestry practice is a grave weakness for our country. Ljusne is the latest sorry example, and further strong reason to fear that our magnificent sawmill industry is an empire with feet of clay. (Svenska Dagbladet, 26 January 1907)

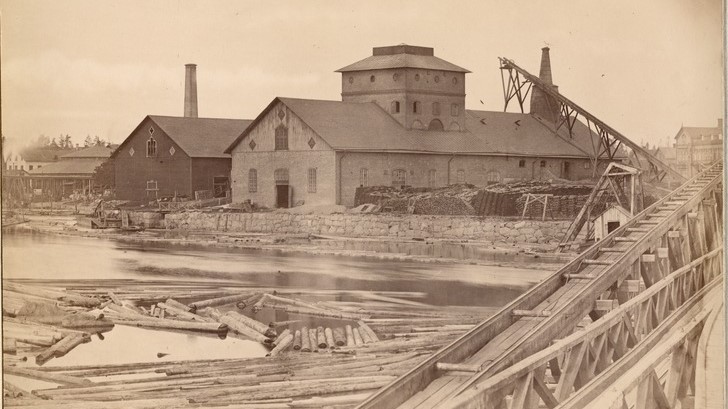

Ljusne-Woxna AB was involved in another issue of the day, namely in the Norrland issue. This concerned the destruction by the forestry companies of the Norrland forests of northern Sweden. When the company let it be known that the sawmill operations at Ljusne would cease from 1 May 1907, due to the fact that the company could not harvest sufficient enough timber from its forests, the news was picked up by the press. The newspapers wrote that Ljusne-Woxna AB, like many other forest companies, had not run their business on the basis of sustainable forestry practices. Large exporting sawmills had been developed and built, but the companies had not given much thought to how long the forest resources they owned and if they would be sufficient over the long-term.

The company defends itself

In response to defend itself against the attacks by the press, in February 1907 the company purchased an advertisement in Aftonbladet in which it responded to the accusations by pointing out that the relationship between the employees and employers had always been good, that so much had been done for the good of the workers, and that the older employees could attest to this. The rifts had arisen only after the formation of the “socialist” youth club. The need to lay off a number of workers after the events at Fejan was explained as follows:

Those we had to dismiss, the two who had signed the telegram and others amongst the Socialist leaders there, were not dismissed because of the telegram, but because of long-term systematic propaganda and incitement at Ljusne. It was therefore simply an act of self-defence. (Aftonbladet, 26 January 1907)

The end

The inquiry set up to shed light on the Ljusne affair was critical on several points. The strength of the company lay in its forest reserves. Therefore it should have invested in modern sawmilling practices and perhaps wood pulp production. This would have helped the company survive through the post-war downturn.

The results of the investigation were crushing for Harry. Since 1912, the development of the company had lacked a well thought-out plan for its development. Harry's expertise was in iron, but his efforts had come at the worst possible time during wartime and recession. Harry let a number of older senior managers go and instead hired fellow classmates from his university days.

Several causes of the company’s crisis lay further back in time, however, and could be related to Walther von Hallwyl’s leadership and also to Wilhelm von Eckermann’s. The company had been led without attention to its business nor and financial prudence, the investigation concluded.