The forest behind it all

Wilhelm Kempe tillhörde en köpmannasläkt från svenska Pommern i norra Tyskland. I flera generationer hade hans förfäder varit borgare och köpmän i bland annat Stralsund där det fanns ett stort antal handelshus. Wilhelm Kempe var son till Carl Bernhard Kempe och hans hustru Anna-Maria Wallis. Av deras sju barn etablerade sig fyra söner som köpmän, två i Sverige och två i Ryssland.

Wilhelm Kempe belonged to a merchant family from Swedish Pomerania in northern Germany. For several generations, his forefathers had been citizens and merchants in, among other places, Stralsund where there were a large number of trading houses. Wilhelm Kempe was the son of Carl Bernhard Kempe and his wife Anna-Maria Wallis. Of their seven children, four sons established themselves as merchants, two in Sweden, and two in Russia.

Johan Carl ran a wholesale, shipbuilding and shipping company in Härnösand; Johann Bernhard was a wholesaler of goods in Saint Petersburg; Ehrenfried Albrecht a landowner and sugar mill owner in Novgorod; while Wilhelm Heinrich began his career as a wholesaler in Stockholm. The youngest son Elias chose the priest’s path and the two daughters married merchants in Stralsund.

Wilhelm Kempe moved to Stockholm when he was only a teen. Sometime around 1823 he was worked as an apprentice for his mother’s brother, uncle Albrecht Wallis. He stayed there for two years after which he moved to Härnösand to work in his brother’s firm Wikner & Co.

At first, Wilhelm Kempe lacked his own financial assets. But he established good contacts and sought out opportunities to work together with businessmen not averse to taking risks. His brother Johan Carl helped him with significant sums of money. In December 1843, Wilhelm Kempe married his cousin Johanna Wallis, and with her came a large dowry.

With this new financial capital, Wilhelm Kempe was able to invest in forests, woodlands that later would generate enormous profits. Wilhelm and Johanna settled in a rented apartment in the Schinkel house at Kornhamnstorg in Stockholm. The apartment with about ten rooms was located on the third floor. The office was on the fourth floor of the same house. The couple had one child, daughter Wilhelmina.

Wilhelmina Kempe married Walther von Hallwyl in 1865. Walther was a nobleman and an officer in the Swiss army. The precondition that Wilhelmina’s parents set for his consent was that Walther von Hallwyl should move to Sweden, which he also did.

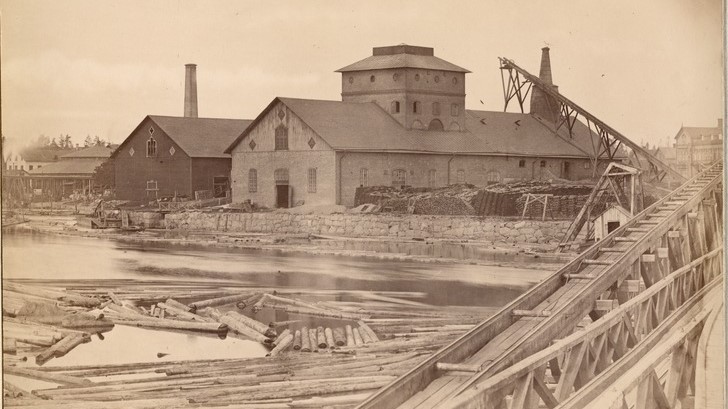

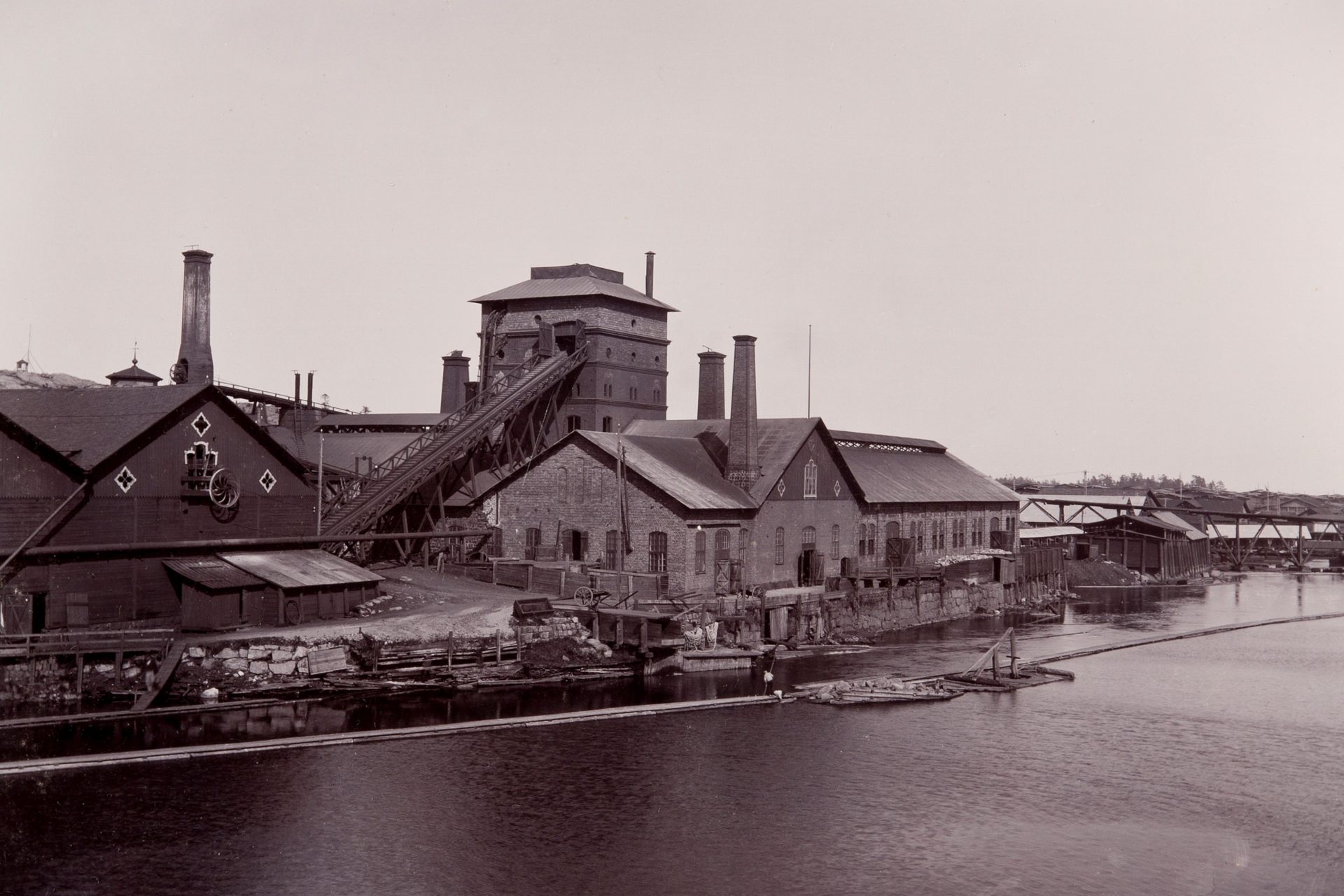

Ljusne-Woxna is established

Like other businessmen, Wilhelm Kempe also had his ups and downs. In 1857 he was close to bankruptcy, but business quickly picked up again and with new investments and modern technology from the 1860s the business grew.

In 1881 Wilhelm Kempe established Ljusne-Woxna AB from his business enterprises. The sawmill, the ironworks and the forest management formed the core of the business activities. The company’s founders were Wilhelm Kempe, his son-in-law Walther von Hallwyl, and office manager Herman Wilms. Kempe owned 646 shares, while Walther von Hallwyl and the company’s manager each owned one share.

At this time, the company’s forest holdings consisted of approximately 300,000 hectares (3,000 km²). In 1875, Sweden’s total exports of sawn timber stood at around 500,000 standards (1 standard = 4.5 cubic metres). In the years 1875 to 1900, it more than doubled. Of these exports, at least one third came from companies in Gävleborg County, where Ljusne-Woxna AB was the area’s largest sawmill. Ljusne-Woxna AB was undoubtedly an important part of the development.

The sawmill supplied the ironworks with cheap charcoal and the ironworks the mechanical workshop with iron, which in turn provided the sawmill with maintenance and manufacture of tools and machines. In the 1880s the company grew even larger. The business was at full capacity and at it peak the number of employees was between 1,000 and 1,500. The production took place in Ljusne and Voxna, but the sale was handled from the head office, the firm Wilh. H. Kempe, in Stockholm

The Hallwyl era

When Walther von Hallwyl married Wilhelmina Kempe, he knew he was marrying into a very wealthy entrepreneurial family. After Wilhelm Kempe’s death in 1883, Walther von Hallwyl became Managing Director. Walther didn’t share his father-in-law’s passion for business. Even though he spent an extensive amount of time in the office, his correspondence we have today is signed mostly by the office managers Herman Wilms and Hugo Holm. These two were also authorised to represent him in business transactions and signing contracts.

If Wilhelm Kempe had been an entrepreneur to the core, Walther von Hallwyl’s leadership could be characterised by formal business management. During his leadership, the company made substantial profits. However instead of investing them in other business activities or holding them in reserve for future use, the money went to donations to charity and for scientific and cultural purposes, and to his personal consumption.

Decline

At the time around the turn of the 20th century, there were rumours that Ljusne-Woxna would be sold. As the conflict between management and workers became increasingly sharp after 1904, Walther von Hallwyl began to think about sales, but Wilhelmina did not want to divide her father’s life’s work. It was offered to his son-in-law Wilhelm von Eckermann, who was married to eldest daughter Ebba, to over as company manager. He initially refused, but then allowed himself to be persuaded on the condition that he first be apprenticed to his father-in-law so that could learn.

Wilhelm von Eckermann joined the company at the beginning of a period of crisis: the great Swedish labour conflict of 1909, the General Strike, then the war years, and then the financial crisis of 1918–1919. During his time, the workers saw a company in decline. Wilhelm von Eckermann’s son Harry was chosen by his grandparents as the company’s future leader. He was pressured by his grandmother to obtain an education as a mountain engineer. When he became chief engineer in 1913, and later manager after his father, Wilhelmina demanded a promise from him never to let the company slip through the family’s fingers and leave its hands. Wilhelmina von Hallwyl’s conviction was that the company her father had established must be continued within the family at all costs. Plus she also opposed major changes within the company.

The end

At the turn of the 20th century, Walther von Hallwyl and his son-in-law Wilhelm von Geijer wanted to sell off the company. It was perhaps that all shareholders, with the exception of the von Eckermann family, were afraid of losing the entire company. The company’s shares had been distributed fairly between the children and consensus prevailed, until November 1919. Ljusne-Woxna AB went into liquidation and the long-time company was dissolved. The majority of the company’s shares had then been sold to a consortium represented by the Centralgruppens Emissionsbolag. The von Eckermann and Wachtmeister families retained their shares. They were behind Harry, and together with the consortium they establishedNya Ljusne-Woxna AB where Harry was appointed Managing Director.