Life in Ljusne

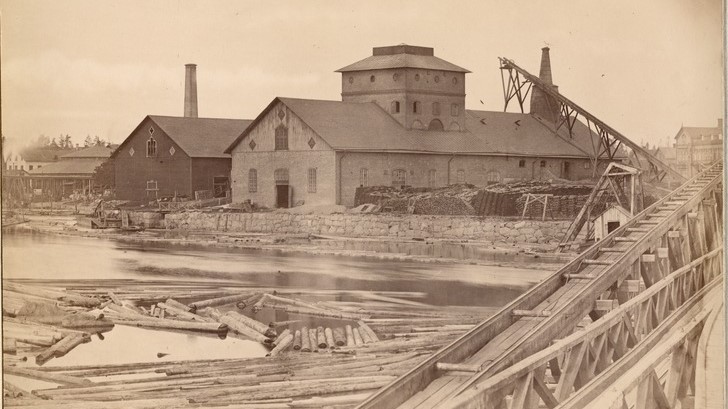

With eleven steam saws along the Ljusnan river on the Söderhamn - Ljusne route, the Söderhamn district was also at the time the country's leading sawmill district. At the end of the 19th century there were daily steamboat services with Söderhamn, Gävle and Stockholm. Here we tell you more about the development of the town and about two major events that are remembered for very different reasons: the royal visit of 1890 and the great timber board yard fire of 1893.

A vibrant community

In Ljusne, there was everything a person could need. In its heyday, the community consisted of industrial buildings, offices, workers’ and servants’ housing, a fire station and a customs house. In addition, there were hotels with servicing meals, a godtemplar room, trading post, church, infirmary, doctor’s office and residence, pharmacy, shooting pavilion and salmon aquaculture. In 1899, a farm was established to supply the workers with dairy products.

In 1885, fire insurance policy was taken out on the buildings in Ljusne that were owned by the company. At that time there were about 200 buildings, 53 of which were workers’ dwellings. Most of them were large barracks and multi-family houses. Adjacent to them were also outbuildings, the privies and wood sheds.

For a family

The workers’ wage included free housing, free firewood (fuel for the stove) and a vegetable garden. Electric lighting, running water and waste water removal was not included. The families were big and lived in cramped and crowded circumstances. In addition, they had to take in lodgers when the seasonal workers arrived. The workers’ housing standards were poor by modern standards, but the conditions at Ljusne and Ala are said to have been better than at many other sawmills at the time.

The provincial medical officer made inspection trips in the district and reported to the public authorities on the general state of health of the population. He reported that overcrowding in Ljusne was not a major problem, as most families had a “room and a kitchen,” meaning one room and kitchen for an entire family.

In 1906, shift work at the sawmill ceased and housing became more available. In 1918, new workers’ housing was built, which according to the then manager Harry von Eckermann was more than necessary.

A residence for summer use

Between 1892 and 1893, Walther von Hallwyl had a new summer villa built next to the river in the vicinity of the sawmill. This was meant to replace one of the two Swiss-style villas built by Wilhelm Kempe in the early 1860s. The old, large residence was moved further up the river where it became a rectory. The smaller residence was left standing and used as a summer residence by the von Eckermann family.

The new building was designed by architect Axel Kumlien. Wilhelmina von Hallwyl wanted to decorate and furnish the new summer home in an informal style. The large glassed-in veranda was furnished with wicker furniture and green plants. From here, there was an excellent view of the garden and the river. Walther von Hallwyl liked to sit in the tower in the evenings, looking out over the sea and gazing at the stars with his astronomical binoculars. The family stayed in this grand home for one month each summer. The house and the church were the only buildings in Ljusne that had electric light at this time.

The Royal visit

One of the highlights of Walther von Hallwyl’s time in charge was certainly the royal visit in August 1890, when Oscar II visited the industries at Ljusne. The fact that the King visited an industry in this part of the country for the first time was a great honour for both the company and the employees, as well as for the settlement itself.

The king arrived with his ship “Drott,” and was welcomed with great pomp and circumstance. The royal cortege passed the timber track on the way to the visit to the workshops. The Royal party climbed Vårdberget, which provided a fine vantage point. There is still Oscar II’s name inscription in the mountain, as a reminder of the visit.

Dinner was served in a large tent in the courtyard at the director’s residence with speeches, music and singing by the attending youth. Before the royal party returned, a large fireworks display was held over the harbour area.

The great fire

On 18 April 1893, the timber board yard in Ljusne burned to the ground. According to the police interviews, the fire broke out shortly after 6 o’clock in the morning in a stack of boards in the timber board yard. There were about 18,000 standard boards there, worth some SEK 2 million. A whole year’s stock that had been prepared for export became the prey of the flames and was destroyed. In addition, 13 electrical adjusters, a timber warehouse, materials sheds, timber board yard office, a barge shed, 62 barges, two rafting docks, a building with 13 barges and almost 2 km of timber yard quays burned to the ground.

The heat was so strong that the iron wheels on a wagon that was standing nearby melted. It wasn’t until 22:00 at night that the fire was brought under control. The timber board yard was quickly rebuilt. The previously high production rate slowed down, however, and the sawing was reduced to 14,000-15,000 standards per year.